C++ shared pointers come up again and again in quant interviews, and for good reason: they sit at the intersection of memory management, performance, ownership semantics, and real-time system reliability, all skills quants are expected to master. In modern C++ codebases used across trading desks, risk engines, and pricing libraries, std::shared_ptr is everywhere, yet many candidates only know the surface-level behavior. Interviewers use shared pointer questions to test whether you understand what’s really happening under the hood: control blocks, atomic reference counting, cache effects, and the subtle performance pitfalls that matter in low-latency environments. They also want to see if you can reason about ownership graphs, detect leaks caused by cycles, and choose correctly between shared_ptr, unique_ptr, and raw pointers in high-frequency workloads. What are the top shared_ptr questions?

Question 1: “What is a Shared Pointer? Give A Quantitative Finance Example”

A shared_ptr is a reference-counted smart pointer that enables shared ownership of a dynamically allocated object, automatically deleting it when the last owner goes away.

In many pricing engines, several components need access to the same yield-curve snapshot without copying it. A shared_ptr is ideal here because it lets each module share ownership safely. Here’s a minimal example:

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include <vector>

struct YieldCurve {

std::vector<double> tenors;

std::vector<double> discountFactors;

YieldCurve() {

std::cout << "YieldCurve built\n";

}

~YieldCurve() {

std::cout << "YieldCurve destroyed\n";

}

};

int main() {

auto curve = std::make_shared<YieldCurve>();

std::cout << "Ref count initially: " << curve.use_count() << "\n";

{

// Risk model shares the same curve

auto riskModelCurve = curve;

std::cout << "Ref count after risk model uses it: "

<< curve.use_count() << "\n";

} // riskModelCurve dies, curve stays alive

std::cout << "Ref count after model finished: "

<< curve.use_count() << "\n";

}What This Example Demonstrates

1. Shared Ownership of a Core Market Object

In real pricing systems, many components—pricing engines, risk calculators, scenario generators—must all access the same yield curve. Using std::shared_ptr ensures the curve persists as long as at least one module still uses it, without forcing expensive deep copies.

2. Reference Counting Behind the Scenes

Each time the shared_ptr is copied (e.g., when the risk model takes a reference), the strong reference count increases. When copies go out of scope, the count decreases. Only when the count reaches zero does the object get destroyed. This is exactly what happens to the YieldCurve instance across scopes in the example.

3. Automatic Lifetime Management (RAII)

You never call delete on the yield curve. Its lifetime is tied to the lifetime of the owning shared_ptr instances.

This reduces the classic risks in large quant codebases: dangling pointers, double deletes, and lifetime mismatches between pricing components.

Question 2: “How does shared_ptr manage reference counting?“

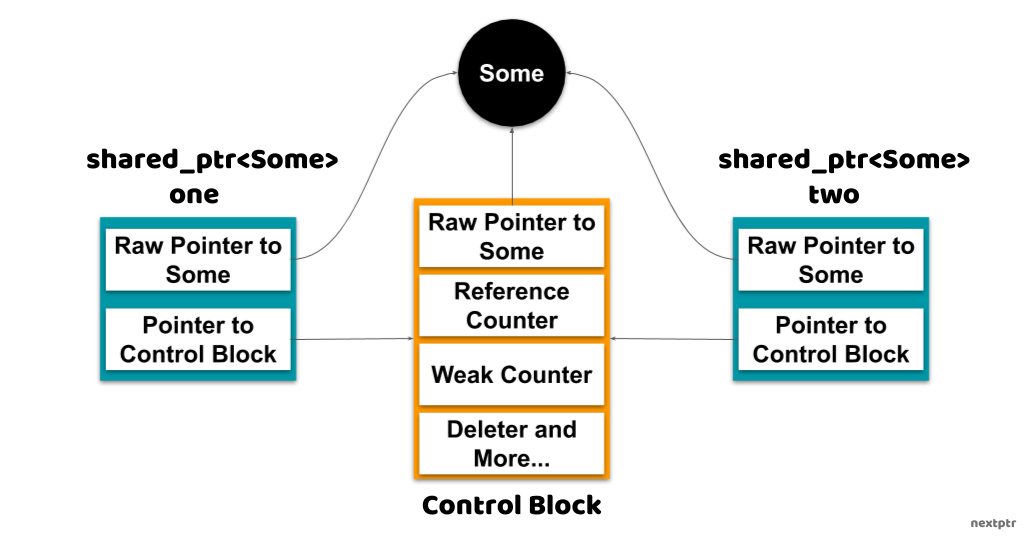

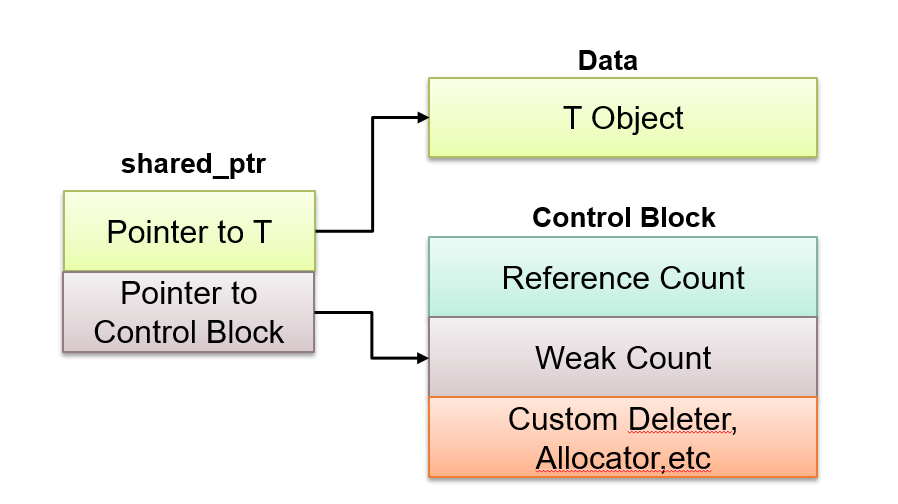

std::shared_ptr uses a separate control block to track how many owners an object has. Every time a shared_ptr is copied, the control block increments a strong reference count. Every time a shared_ptr is destroyed or reset, that count is decremented. When the strong count reaches zero, the managed object is automatically deleted.

Under the hood, the control block stores:

- A strong reference count

(number of activeshared_ptrowning the object) - A weak reference count

(number ofweak_ptrobserving the object) - The managed pointer

- (Optionally) a custom deleter and allocator

All reference count updates are atomic, which makes shared_ptr safe to use across threads—though more expensive than unique_ptr. In practice, this mechanism ensures that shared market objects (like yield curves, volatility surfaces, or trade graphs) live exactly as long as the last component using them, with no need for manual delete and no risk of premature destruction. One of the top shared_ptr questions!

Question 3: “What causes a memory leak with shared_ptr?“

A memory leak with std::shared_ptr happens when two or more objects form a cyclic reference, meaning each holds a shared_ptr to the other, so their reference counts never drop to zero and their destructors never run.

For example, if struct A has std::shared_ptr<B> b; and struct B has std::shared_ptr<A> a;, creating the cycle a->b = b; and b->a = a; will leak both objects because each keeps the other alive. The fix is to use std::weak_ptr on one side of the relationship.

struct B;

struct A { std::shared_ptr<B> b; };

struct B { std::shared_ptr<A> a; }; // ← this creates a cycle and leaks

auto a = std::make_shared<A>();

auto b = std::make_shared<B>();

a->b = b;

b->a = a; // reference counts never reach 0 → leakHere’s the same idea but fixed using std::weak_ptr so the cycle doesn’t keep the objects alive:

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

struct B;

struct A {

std::shared_ptr<B> b;

~A() { std::cout << "A destroyed\n"; }

};

struct B {

std::weak_ptr<A> a; // weak_ptr breaks the cycle

~B() { std::cout << "B destroyed\n"; }

};

int main() {

auto a = std::make_shared<A>();

auto b = std::make_shared<B>();

a->b = b;

b->a = a; // does NOT increase refcount

return 0; // both A and B are destroyed normally

}

That's one of the top shared_ptr questions.

Question 4: make_shared vs. shared_ptr<T>(new T): what’s the difference?

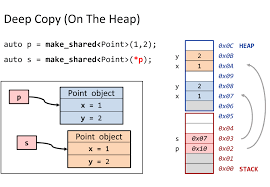

std::make_shared<T>() and std::shared_ptr<T>(new T) both create a shared_ptr, but they differ in performance, memory layout, and exception-safety:

- make_shared is faster and uses one allocation: it allocates the control block and the object in a single heap allocation, improving cache locality.

- shared_ptr<T>(new T) uses two allocations: one for the control block and one for the object, making it slower and more memory hungry.

- make_shared is exception-safe: if constructor arguments throw, no memory is leaked. With

shared_ptr<T>(new T), if you add custom deleters or wrap logic incorrectly, leaks can occur. - make_shared is preferred except when you need a custom deleter or want separate lifetimes for control block and object (rare—e.g., weak-to-shared resurrection edge cases).

Example:

auto p1 = std::make_shared<MyObject>(); // one allocation, safe

auto p2 = std::shared_ptr<MyObject>(new MyObject()); // two allocationsQuestion 5: Why is shared_ptr slower?

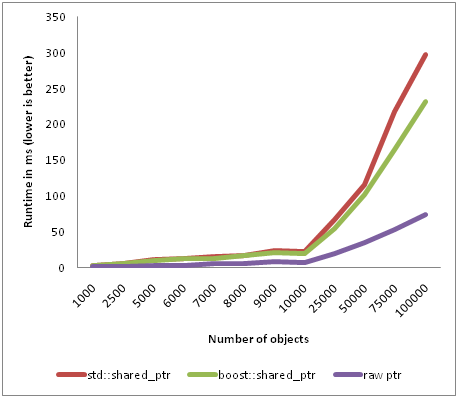

std::shared_ptr is slower because it performs atomic reference counting, extra bookkeeping, and sometimes extra allocations to manage shared ownership. Every copy of a shared_ptr must atomically increment the control block’s reference count, and every destruction must atomically decrement it; these atomic operations create contention, inhibit compiler optimizations, and add CPU overhead. A shared_ptr also maintains both a strong and weak count, uses a control block to track them, and may require separate heap allocations (unless created via make_shared). This combination of atomic ops + bookkeeping + heap activity makes shared_ptr significantly slower than a raw pointer or even a unique_ptr, which performs no reference counting at all.