What’s XVA? In modern derivative pricing, that question sits at the heart of almost every trading, risk, and regulatory discussion. XVA, short for X-Value Adjustments, refers to the suite of valuation corrections applied on top of a risk-neutral price to reflect credit risk, funding costs, collateral effects, and regulatory capital requirements. After the 2008 financial crisis, these adjustments evolved from a theoretical curiosity to a cornerstone of real-world derivative valuation.

Banks today do not quote the “clean” price of a swap or option alone; they quote an XVA-adjusted price. Whether the risk comes from counterparty default (CVA), a bank’s own credit (DVA), collateral remuneration (COLVA), the cost of funding uncollateralized trades (FVA), regulatory capital (KVA), or initial margin requirements (MVA), XVA brings all these effects together under a consistent mathematical and computational framework.

1.What is XVA? The XVA Family

XVA is a collective term for the suite of valuation adjustments applied to the theoretical, risk-neutral price of a derivative to reflect real-world constraints such as credit risk, funding costs, collateralization, and regulatory capital. In practice, the price a bank shows to a client is not the pure model price but the XVA-adjusted price, which embeds all these effects into a unified framework.

Modern XVA desks typically decompose the total adjustment into several components, each capturing a specific economic cost or risk. Together, they form the XVA family:

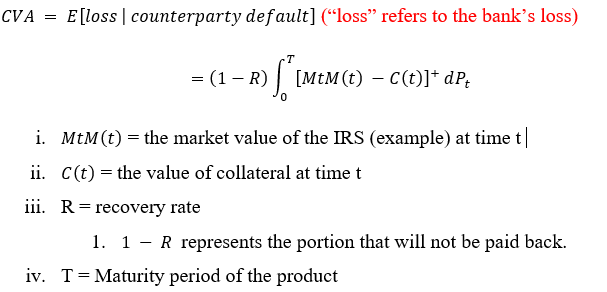

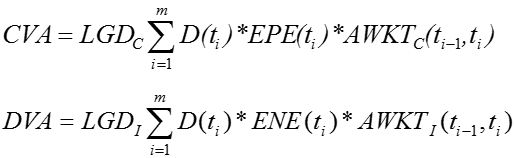

CVA – Credit Value Adjustment

CVA is the expected loss due to counterparty default. It accounts for the possibility that a counterparty may fail while the exposure is positive. Mathematically, it is the discounted expectation of exposure × loss-given-default × default probability. CVA became a regulatory requirement under Basel III and is the most widely known XVA component.

DVA – Debit Value Adjustment

DVA mirrors CVA but reflects the institution’s own default risk. If the bank itself defaults while the exposure is negative, this creates a gain from the perspective of the shareholder. While conceptually symmetric to CVA, DVA cannot usually be monetized, and its inclusion depends on accounting standards.

FVA – Funding Value Adjustment

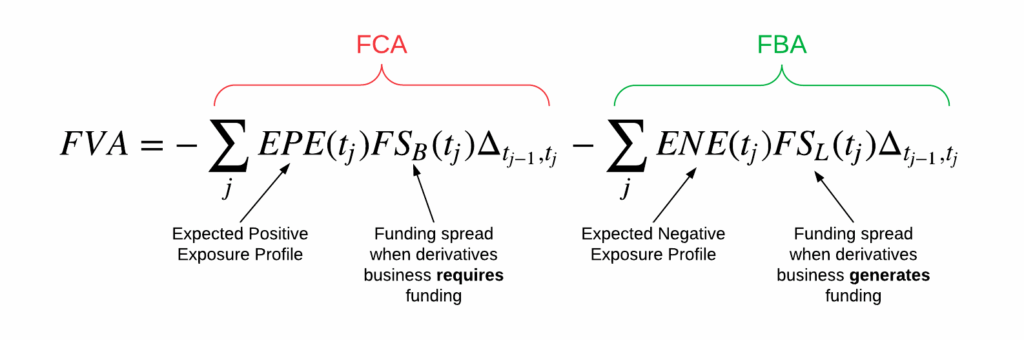

FVA measures the cost of funding uncollateralized or partially collateralized positions.

It arises from asymmetric borrowing and lending rates: funding a derivative generally requires borrowing at a spread above the risk-free rate, and this spread becomes part of the adjusted price. FVA is highly institution-specific, sensitive to treasury curves and liquidity policies.

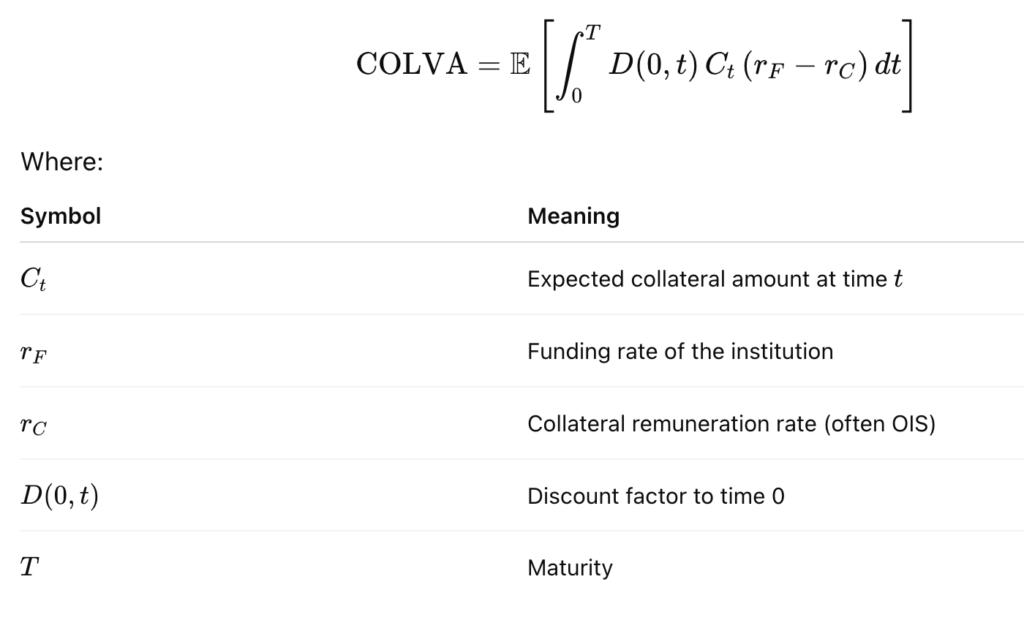

COLVA – Collateral Value Adjustment

COLVA captures the economic effect of posting or receiving collateral under a Credit Support Annex (CSA). It reflects the remuneration of the collateral account and the mechanics of discounting under different collateral currencies.

MVA – Margin Value Adjustment

MVA represents the cost of posting initial margin, particularly relevant for centrally cleared derivatives and uncleared margin rules. Since initial margin is locked up and earns little, MVA quantifies the funding drag associated with this constraint.

[math]

\large

\text{MVA} = -\int_0^T \mathbb{E}[\text{IM}(t)] , (f(t) – r(t)), dt.

[/math]

KVA – Capital Value Adjustment

KVA measures the cost of regulatory capital required to support the trade over its lifetime. Because capital is not free, banks incorporate a charge to account for the expected cost of holding capital against credit, market, and counterparty risk.

A commonly used representation of KVA is the discounted cost of holding regulatory capital K(t)K(t)K(t) over the life of the trade, multiplied by the bank’s hurdle rate hhh (the required return on capital):

[math]

\large

\text{KVA} = -\int_0^T D(t), h, K(t), dt

[/math]

where:

- K(t) is the projected regulatory capital requirement at time t (e.g., CVA capital, market risk capital, counterparty credit risk capital),

- h is the hurdle rate (often 8–12% depending on institution),

- D(t) is the discount factor,

- T is the maturity of the trade or portfolio.

2.The Mathematics of XVA

Mathematically, XVA extends the classical risk-neutral valuation framework by adding credit, funding, collateral, and capital effects directly into the pricing equation. The total adjusted value of a derivative is typically expressed as:

[math]

V_{\text{XVA}} = V_0 + \text{CVA} + \text{DVA} + \text{FVA} + \text{MVA} + \text{KVA} + \cdots

[/math]

where V0 is the clean, risk-neutral price. Each adjustment is computed as an expectation under a measure consistent with the institution’s funding and collateral assumptions. CVA, for example, is the expected discounted loss from counterparty default.

Because these adjustments are interdependent, the pricing problem is no longer a simple additive correction to the clean value but a genuinely nonlinear one. Funding costs depend on expected exposures, exposures depend on default and collateral dynamics, and capital charges feed back through both. The full XVA calculation therefore takes the form of a fixed-point problem in which the adjusted value appears inside its own expectation. In practice, modern XVA desks solve this system using large-scale Monte Carlo simulations with backward induction, ensuring that all components—credit, funding, collateral, and capital—are computed consistently under the same modelling assumptions. This unified approach captures the true economic cost of trading and forms the mathematical backbone of XVA analytics in industry.

3.Calculate xVA in C++

To make the discussion concrete, we can wrap a simple XVA engine into a small, header-only C++ “library” that you can drop into an existing pricing codebase. The idea is to assume that exposure profiles and curves are already computed elsewhere (e.g. via a Monte Carlo engine) and focus on turning those into CVA, DVA, FVA, and KVA numbers along a time grid.

Below is a minimal example. It is not production-grade, but it shows the structure of a clean API that you can extend with your own models and data sources.

// xva.hpp

#pragma once

#include <vector>

#include <functional>

#include <numeric>

namespace xva {

struct Curve {

// Discount factor P(0, t)

std::function<double(double)> df;

};

struct SurvivalCurve {

// Survival probability S(0, t)

std::function<double(double)> surv;

};

struct XVAInputs {

double V0; // clean (risk-neutral) price

Curve discount;

SurvivalCurve counterpartySurv;

SurvivalCurve firmSurv;

std::vector<double> timeGrid; // t_0, ..., t_N

std::vector<double> expectedPositiveEE; // EPE(t_i)

std::vector<double> expectedNegativeEE; // ENE(t_i)

double lgdCounterparty; // 1 - recovery_C

double lgdFirm; // 1 - recovery_F

double fundingSpread; // flat funding spread (annualised)

double capitalCharge; // flat KVA multiplier (for illustration)

};

struct XVAResult {

double V0;

double cva;

double dva;

double fva;

double kva;

double total() const {

return V0 + cva + dva + fva + kva;

}

};

// Helper: simple forward finite difference for default density

inline double defaultDensity(const SurvivalCurve& S, double t0, double t1) {

double s0 = S.surv(t0);

double s1 = S.surv(t1);

if (s0 <= 0.0) return 0.0;

return (s0 - s1); // ΔQ ≈ S(t0) - S(t1)

}

inline XVAResult computeXVA(const XVAInputs& in) {

const auto& t = in.timeGrid;

const auto& EPE = in.expectedPositiveEE;

const auto& ENE = in.expectedNegativeEE;

double cva = 0.0;

double dva = 0.0;

double fva = 0.0;

double kva = 0.0;

std::size_t n = t.size();

if (n < 2 || EPE.size() != n || ENE.size() != n)

return {in.V0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0};

for (std::size_t i = 0; i + 1 < n; ++i) {

double t0 = t[i];

double t1 = t[i + 1];

double dt = t1 - t0;

double dfMid = in.discount.df(0.5 * (t0 + t1));

double dQcp = defaultDensity(in.counterpartySurv, t0, t1);

double dQfm = defaultDensity(in.firmSurv, t0, t1);

double EPEmid = 0.5 * (EPE[i] + EPE[i+1]);

double ENEmid = 0.5 * (ENE[i] + ENE[i+1]);

// Simplified discretised formulas:

cva += dfMid * in.lgdCounterparty * EPEmid * dQcp;

dva -= dfMid * in.lgdFirm * ENEmid * dQfm;

// FVA and KVA: toy versions using EPE as proxy for funding/capital.

fva -= dfMid * in.fundingSpread * EPEmid * dt;

kva -= dfMid * in.capitalCharge * EPEmid * dt;

}

return {in.V0, cva, dva, fva, kva};

}

} // namespace xva

An example of usage:

#include "xva.hpp"

#include <cmath>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

using namespace xva;

XVAInputs in;

in.V0 = 1.0; // clean price

// Flat 2% discount curve

in.discount.df = [](double t) {

double r = 0.02;

return std::exp(-r * t);

};

// Simple exponential survival with constant intensities

double lambdaC = 0.01; // counterparty hazard

double lambdaF = 0.005; // firm hazard

in.counterpartySurv.surv = [lambdaC](double t) {

return std::exp(-lambdaC * t);

};

in.firmSurv.surv = [lambdaF](double t) {

return std::exp(-lambdaF * t);

};

// Time grid and toy exposure profiles

int N = 10;

in.timeGrid.resize(N + 1);

in.expectedPositiveEE.resize(N + 1);

in.expectedNegativeEE.resize(N + 1);

for (int i = 0; i <= N; ++i) {

double t = 0.5 * i; // every 6 months

in.timeGrid[i] = t;

// Toy exposures: decaying positive, small negative

in.expectedPositiveEE[i] = std::max(0.0, 1.0 * std::exp(-0.1 * t));

in.expectedNegativeEE[i] = -0.2 * std::exp(-0.1 * t);

}

in.lgdCounterparty = 0.6;

in.lgdFirm = 0.6;

in.fundingSpread = 0.01;

in.capitalCharge = 0.005;

XVAResult res = computeXVA(in);

std::cout << "V0 = " << res.V0 << "\n"

<< "CVA = " << res.cva << "\n"

<< "DVA = " << res.dva << "\n"

<< "FVA = " << res.fva << "\n"

<< "KVA = " << res.kva << "\n"

<< "V_XVA = " << res.total() << "\n";

return 0;

}

This gives you:

- A single header (

xva.hpp) you can drop into your project. - A clean

XVAInputs → XVAResultinterface. - A place to plug in your own discount curves, survival curves, and exposure profiles from a more sophisticated engine.

You can then grow this skeleton (multi-curve setup, CSA terms, stochastic LGD, wrong-way risk, etc.) while keeping the same plug-and-play interface.

4.Conclusion

XVA has transformed derivative pricing from a clean, risk-neutral exercise into a fully integrated measure of economic value that accounts for credit, funding, collateral, and capital effects. The mathematical framework shows that these adjustments are not isolated add-ons but components of a coupled, nonlinear valuation problem. In practice, solving this system requires consistent modelling assumptions, carefully constructed exposure profiles, and scalable numerical methods.

The C++ snippet provided in the previous section illustrates how these ideas translate into a concrete, plug-and-play engine. Although simplified, it captures the essential workflow used on modern XVA desks: compute discounted exposures, combine them with survival probabilities and cost curves, and aggregate the resulting adjustments into a unified valuation.

As models evolve and regulatory requirements tighten, XVA will continue to shape how financial institutions assess the true cost of trading. A solid understanding of its mathematical foundations and computational techniques is therefore indispensable for quants and risk engineers looking to build accurate, scalable, and future-proof pricing systems.